Samuel A. Roberts

By Tim Davis, North Texas eNews, January 2014

The Life and Times of Samuel A. Roberts

Samuel A. Roberts and the Eggnog Riot In 1842

Samuel Roberts and his young bride, Lucinda, made Bonham, then known as Bois d’ Arc, their home. Over the next thirty years Samuel made his mark on the city as a lawyer. In that time he watched Texas go from a republic to a state, got directly involved in the politics of the 1850s that led to the Civil War, and participated firsthand in the war as a Confederate officer and administrator.

As interesting as all of that is, perhaps even more remarkable is the biography that Roberts amassed before setting foot in Bonham. It included getting appointed to West Point only to help create a stir that angered officials all the way to the White House. Moreover, after moving with his parents to Texas in 1838, he eventually managed to land a prominent government post after a childhood friend became president of the young republic.

Samuel Alexander Roberts was born on February 13, 1809 to Dr. Willis and Asenath Roberts of Putnam County, Georgia. When he was ten, the family moved to the Alabama Territory, soon to become a state, to the proposed city of Cahawba in Dallas County.

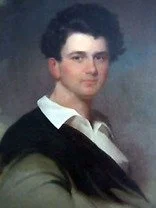

At the age of fifteen Roberts managed to earn an appointment to the United States Military Academy at West Point. A member of the class of 1824, he was among cadets whose names became household words thanks mainly to the Civil War: Jefferson Davis, Robert E. Lee, Ethan Allen Hitchcock and many others.

In late 1826 Samuel Roberts and several others managed to ruin their West Point education by fooling with one of man’s oldest shortcomings – alcohol.

On Christmas Eve a group of cadets decided that their Christmas break should be celebrated with a little eggnog. To get the whiskey needed, Roberts and a handful of others left the post, a violation in itself, and went a couple of miles south to Buttermilk Falls and a place called Haven’s Tavern. After buying the required spirits, they snuck back on post. Before long the eggnog was flowing in both the north and south barracks.

Commanders previously warned that drinking during past holiday breaks had gotten out of hand. When they got word that liquor was being drank on the post again, they went to the barracks and investigated. What followed was a brawl between commanders and intoxicated cadets. The whole affair became known as The Eggnog Riot.

In his excellent account of the event entitled The Eggnog Riot (Presidio Press, 1979), writer and former military man James B. Agnew recorded the details. For the purposes of this piece, I will recount only events related to Samuel Roberts.

Problems began around five o’clock Christmas morning when two West Point officers, Ethan Allen Hitchcock and William A. Thornton, were inspecting the north barracks where Roberts and other cadets were partying. Upon entering, Hitchcock encountered an intoxicated Jefferson Davis. He placed him under arrest and ordered him to his room. (This actually benefited Davis; it kept him out of the worst of the rioting and lessened his ultimate punishment, allowing him to become a West Point graduate. Details can be found in Vol. 1 of The Papers of Jefferson Davis [LSU Press].)

In the meantime, Lt. Thornton continued his inspection. A drunken Samuel Roberts, aware of Thornton’s location and armed with sticks of firewood, waited for him to descend a set of stairs. James Agnew describes what followed:

Thornton started down the stairs. The lantern he carried lighted his figure against the dark window at the top of the stairwell. Roberts threw the wood as hard as he could at the lieutenant. He heard a groan, then the sound of glass breaking. Thornton fell to the stairs and the lamp went out.

Roberts committed the worst crime of all: He assaulted a commissioned officer. (In addition, Vol. 1 of The Papers of Jefferson Davis contains testimony from one cadet stating that he overheard Cadet Roberts “remark that he [Roberts] had thrown a tub - referring to the time of the riot.”)

The legal proceedings against Roberts and other cadets involved in the Eggnog Riot began on January 24 and extended through May 3, 1827. Roberts’ trial was held on February 26th.

“The principal charges” brought against Roberts, writes James Agnew, were “introducing spirituous liquors into the barracks, and mutinous conduct, specifically assaulting a commissioned officer.”

The trial, according to James Agnew:

[M]oved expeditiously through the twenty-eighth, but the court granted Roberts until March 2 to present his final defense summation. Roberts took about thirty minutes to concede to the court that he had been absent from the Academy as charged and attempted to use legal legerdemain to prove that he was being charged for mutinous conduct on hearsay evidence alone. His final argument, using Christ’s crucifixion as analogous with his own case, was an imaginative, if desperate, ploy for sympathy and mercy. “But as the whole human race have been once conditionally pardoned for rebellion against the Almighty, why may not I as an individual (even had all the charges been proven) hope for the same . . .”

His pleas having fallen on deaf ears, in March the court martial ordered Roberts “dismissed from the service of the United States.”

In short, Samuel Roberts was expelled from West Point and the U. S. military. Several other cadets suffered the same fate.

Agnew further notes that “the records of the court of inquiry and the courts-martial were [forwarded] to Washington where they were reviewed by . . . then Secretary of War James Barbour.” He further notes that since “a number of the cases carried sentences of dismission, in late April, Barbour delivered the trial records to the office of President John Quincy Adams.”

President Adams ultimately wrote a lengthy opinion on the matter, which concluded:

The confirmation of so many sentences of dismission from the Academy, of Young Men from whom their Country had a right to expect better things, is an act of imperious though painful duty. Of duty the more painful, because it has not escaped the attention of the President, that the penalty bears not merely upon the transgression, but, upon the prospects of the offenders and upon the cherished expectations of virtuous parents and friends. Convinced, that these considerations must yield to the necessity of a rigorous example, he hopes it will not be lost upon the Youth remaining at the Academy; that they will be admonished to the observance of all their duties by the reflection that when violated by them, while the offense is imputable only to themselves, the punishment must of necessity be shared with them by the dearest of their friends.

(Signed) John Quincy Adams

Washington 3rd May 1827

It seems possible that once Roberts became a fixture in Bonham, he may have casually discussed his time at West Point minus the details about the Eggnog Riot, thus allowing his fellow Bonhamites to consider him a graduate of the esteemed academy. A clue appeared in the March 6, 1909 Bonham Daily Favorite when Judge W. A. Evans wrote of his close relationship with Roberts, which included sharing a law office with him on the north side of the square for many years. He described him as “a graduate of West Point . . . .”

If Roberts did tell Evans or any other friends the truth about his West Point days, he must have sworn them to secrecy.

The Roberts family moves to Texas

As noted in my previous piece, in the spring of 1819 Dr. Willis Roberts decided to move his family, including his son and future Bonham lawyer Samuel Roberts, from Georgia to Alabama and to the city of Cahawba, in Dallas County.

Joining the Roberts family for the move was a young man, barely twenty, from the neighboring Georgia community of Fairfield Plantation. His name was Mirabeau Buonaparte Lamar, and he intended to help the Roberts family in operating a general store in Cahawba. In his biography of Lamar entitled The Life and Poems of Mirabeau B. Lamar,Philip Graham noted: “For the next year Mirabeau became a member of the Roberts household. He found the large family a replica of his own at Fairfield.” No one could have foreseen the future awaiting Lamar roughly seventeen years later in the newly formed Republic of Texas.Unfortunately for Willis Roberts and Mirabeau Lamar, their store did not flourish. “[T]he mercantile business,” wrote Philip Graham, “did not thrive. Such heavily capitalized firms as Cocheran and Perine had set a standard far beyond the reach of the rather meager means of Roberts and Lamar.”

After just one year, Willis Roberts gave up and moved his family to Mobile. Lamar stayed in Cahawba working for the local newspaper. By early 1822, however, he also needed a change of scenery, and so returned to Georgia.

In no time Lamar found himself in the big middle of Georgia politics and government when he was appointed personal secretary to the newly-elected governor, George M. Troup.

In January 1826 he added to his good fortune when he married a young lady from Twiggs County named Tabitha Jordan.

While Lamar’s return to Georgia held lots of promise, dark clouds loomed on the horizon. In 1830 Lamar’s young bride succumbed to tuberculosis. A short four years later his beloved brother, Lucius Lamar, committed suicide. Once again it seemed that Georgia was not the place for Mirabeau Lamar.

Reading of exciting events in Texas from his old friend and former Georgia citizen, James Fannin, Lamar headed west, ostensibly to do historical research on the events unfolding in the Mexican province.

Mirabeau Lamar arrived in Nacogdoches in July 1835. He ultimately found himself caught up in the Texas revolution. By April 1836 he was helping Sam Houston in the defeat of Santa Anna and his forces at San Jacinto.

On October 22, 1836, Lamar was sworn in as the first vice-president of the new Republic of Texas, under President Sam Houston.

By April 1837 Lamar was ready for a break from the previous year’s adventure. He set out on a vacation trip to Georgia to visit family and friends. He was greeted with public dinners and military receptions; the people of Georgia were proud that their native son was the vice-president of the continent’s newest nation.

Interestingly, Lamar stayed away from his new country for quite some time. He didn’t start back to Texas until October, and along the way he made at least one stop.

“At Mobile,” wrote Philip Graham, “there was another public dinner, which turned out to be the manifestation of Alabama good feeling and sympathy for Texas.” Moreover, Graham noted that while in Mobile “Lamar renewed his acquaintance with his old friends, the Roberts family . . . .”

After Lamar’s visit to Mobile, the Roberts family stayed in contact with him by mail. The correspondence between various members of the family and Lamar is relatively easy to track. Copies of letters are found in various Lamar biographies, and in the six-volume Papers of Mirabeau B. Lamar (a complete set of which can be found at The Sam Rayburn Library).

In a letter dated April 14, 1838, Samuel Roberts tells Lamar of the Roberts family’s strong desire to leave Mobile and move to Texas. “I am myself interested in nothing save Texas,” wrote Samuel.

In another letter dated May 12, Willis Roberts informed Lamar of “the settlement of business preparatory to the removal to Texas.”By July 12 Willis informed Lamar that he had his new house in Texas “up and nearly [e]nclosed . . . .” The letter shows to have been sent from Aransas.

In December 1838 Lamar became President of the Republic of Texas. In no time at all the spoils trickled down to the Roberts family. Lamar biographer Philip Graham noted that to Willis Roberts and his three sons (Samuel, Joel and Reuben), “Lamar was to give a total of five Texas offices.”

In January 1839 Willis was appointed chief Collector of Customs for the port of Galveston. (In naming Willis to that post, Lamar removed Gail Borden from the same. Some thought the move unfair and argued that it smelled of pure politics. Borden went on to many business ventures, including perfecting the process for making condensed milk.) Moreover, the Texas State Handbook notes that Samuel Roberts was appointed “notary public of Harrisburg County on January 23, 1839 [and] secretary of the Texas legation to the United States in March 1839 . . . .”

As secretary of the Texas legation, Samuel lived for a while in Washington D.C. Many letters were exchanged between Lamar and Roberts relative to many key political issues of the day, including any attempts by the United States to annex Texas as another state.

In a letter dated October 16, 1839 from a John S. Evans to Lamar, the resignation of Roberts as “Secretary of the Legation to the United States . . .” is mentioned, with Evans lobbying to be his replacement.

In the spring of 1840 Samuel Roberts made his way back to Texas in the hopes of establishing a law practice.

There is little evidence as to whether or not Samuel was successful at practicing law. What is certain is that by the spring of 1841 Willis Roberts was lobbying Lamar for another government job for his son. In a letter dated April 12, he asked Lamar about a possible diplomatic post for Samuel.

The request did not go unnoticed. By May 25 Samuel was appointed acting Secretary of State for the Republic of Texas. Shortly afterwards he found himself conveying Lamar’s wishes to the men who left in June for the ill-fated Santa Fe Expedition. Instructions to the men “were signed in Lamar’s absence by Samuel A. Roberts, acting secretary of state,” wrote historian Noel Loomis in his book The Texan-Santa Fe Pioneers.

The Texas State Handbook notes that on September 7 Samuel Roberts was promoted to Secretary of State for the Republic of Texas, a post he undoubtedly held until the Lamar Administration left office in January 1842.

Samuel A. Roberts moves to Fannin County

Not long after the Lamar Administration left office, Samuel A. Roberts, Secretary of State for the Republic of Texas towards the end of Mirabeau Lamar’s presidency, found himself in Fayette County getting married to the widow Lucinda Reed on April 8, 1842.

Afterwards the couple moved to Bonham at the urging of Samuel’s brother-in-law, Palmer J. Pillans, and his wife, Laura (Samuel’s sister). Pillans, using Bonham as his headquarters, was working as a field agent attempting to colonize land in north Texas for the well-known Charles Fenton Mercer.

In an unpublished autobiography, Pillans noted that Samuel and Lucinda moved to Bonham “[a]t my suggestion” and that Samuel “settled there and did well.”

Pillans, also a lawyer, apparently squared off against his brother-in-law at some point in a Fannin County courtroom.

“While at the bar at Bonham,” he wrote to a relative, “it gave me infinite pleasure to defeat your uncle Sam . . . in a case.” (In 1849 the Pillans left Bonham and headed west, settling in Santa Fe. By 1853 they settled in the town that Laura once called home, Mobile, Alabama.)

By the late 1840s, after Texas joined the Union as its twenty-eighth state, Samuel A. Roberts got involved in politics. Joining the Whig party, he became a delegate to local, state and national conventions in 1848 and 1852. Through law and politics, Roberts was quickly making a name for himself locally.

As an active politician, Roberts could not avoid the hottest debate topic of the late 1850s - the future of slavery. Some considered Fannin County one of the places where an anti-slavery movement might take root in Texas. And it was up to local defenders of the “peculiar institution” to block such a movement.

One key institution suspected of fomenting abolitionist sentiments in the county was the Methodist Episcopal Church of North Texas. In his coverage of the subject that appeared in the January 1965Southwestern Historical Quarterly, historian Wesley Norton noted that the “area of the principal activity of the Methodist Episcopal Church in Texas included Johnson, Fannin, Denton, Grayson, [Kaufman], and Collin counties with the largest congregation from the beginning being located at Bonham.” The entire area was known as the Texas Mission District.

Norton further noted that in 1855 the “Arkansas Annual Conference had met . . . at a school house on Timber Creek near Bonham, Texas, and one of its actions was to complete the formal organization of the Texas Mission District.”

When it was announced that the Arkansas Annual Conference would meet again at the same schoolhouse on Timber Creek in 1859, North Texans became alarmed. Citizens from as far away as Collin and [Kaufman] counties met and called on their counterparts in Fannin County to inform the conference that anti-slavery rhetoric would not be tolerated.

The conference began on Friday March 11, and on Saturday morning a group of Fannin County citizens met at the courthouse to plan their opposition to it. There were many speakers, among them Samuel A. Roberts, who charged the church conference with advocating abolitionist sentiments and perhaps encouraging slave rebellion. Other speakers argued that similar conferences held in the north laid the groundwork for such activity.

As the courthouse meeting dragged on, a committee of three men composed of Roberts, John M. Crane, editor of the local Bonham Independent, and a General Green “were appointed to retire and draft appropriate resolutions” attacking the Methodist Episcopal conference. (Norton shows that newspaper and church accounts, printed in Methodist Episcopal publications, of the events always referred to Roberts as “Judge” Roberts, with the term judge always in quotation marks. Perhaps he was a local judge at the time?)

“The resolutions,” Norton further wrote, “effectively summarized the views and feelings which had been expressed in the public assembly. Secret foes, intent upon the destruction of slavery, lurked among the citizens of Fannin County.” The resolutions were:

to be implemented by a suitable committee sent to “warn them to withhold the further prosecution of said conference, as its continuance will be well calculated to endanger the peace of this community.” The assembly bound itself further to “suffer no public expression of abolition doctrines or sentiments . . . to go unpunished.” A committee of fifty was to confront the conference on Timber Creek with the decision ordering “the discontinuance of their meetings in this county, henceforth and forever.”

According to Norton, the committee of fifty, with Samuel A. Roberts apparently acting as a key spokesperson, went to the conference and presented their demands. Conference leaders replied that they simply wanted to hold a peaceful meeting, just as they had four years earlier. Reason prevailed, and there was no violent confrontation. The Methodist Episcopal conference adjourned on Monday morning as planned without incident.

The committee of fifty, however, was not through condemning the conference. According to Norton, it “made a report to the citizens of the Bonham area on Monday, March 14.” Norton wrote:

Old evidence against the Methodist Episcopal Church and its personnel was recounted and amplified. Once more resolutions of northern conferences were read – resolutions denouncing slavery, recommending that ministers work through the pulpit and the ballot box to accomplish extirpation, and urging that they circulate anti-slavery literature.

Other Bonham notables such as Gideon Smith and state legislator Robert H. Taylor also criticized the Methodist Episcopals for spreading abolitionist sentiments.

Roughly twenty months later, irreconcilable differences over slavery and a host of secondary issues hurled the country into civil war following the 1860 election of Abraham Lincoln to the presidency. As a result, Samuel A. Roberts found himself facing new responsibilities and renewing at least one old acquaintance.

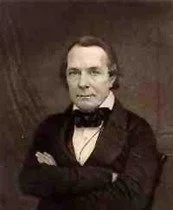

(Correction to my previous piece: In my piece on Dr. Willis Roberts and family moving to Texas, I wrote that Dr. Roberts moved his family from Cahawba to Mobile, Alabama in 1820. That was based on information from Philip Graham’s biography on Mirabeau B. Lamar. A Roberts researcher has since informed me that good evidence shows the move from Cahawba to Mobile actually took place in 1824.) All images used thus far in the Samuel Roberts articles have been courtesy of Sarah Taliferro, a Roberts family descendant.Thanks to Roy Isbell, a Roberts researcher, for information from the unpublished biography of Palmer J. Pillans.

Samuel A. Roberts and the Civil War

As the 1850s rolled into the year 1860, it became clear that the country was sharply divided, politically speaking, and was perhaps headed towards civil war. The election of Abraham Lincoln as President sealed the deal. For southerners, Lincoln in the White House was simply unacceptable, and by late April 1861 eleven states had seceded from the Union.

A couple of months earlier Samuel A. Roberts’ former West Point classmate, Jefferson Davis, took the oath of office to be the leader of the new country, the Confederate States of America.

According to family research records, it wasn’t long before Davis appointed Roberts an assistant adjutant general, basically an administrative position, in the Confederate Army. Civil War records indicate the same. For example, The Papers of Jefferson Davis (LSU Press) contains a general description of a letter, from Roberts to Davis, dated April 2, 1862, which mentions Roberts being named “assistant adjutant general” and tells Davis of the disorganized nature of cavalry recruiting in Texas. The description reads:

From Samuel A. Roberts . . . West Point classmate writes from Bonham, Texas, complaining that his efforts to raise five cavalry regiments have been stymied by others’ recruiting mounted units; was assured, when commissioned assistant adjutant general, that his would be the only cavalry regiments received from Texas; without an organized recruiting policy, state volunteers have ‘gone off – helter-skelter, mounted on every description of animal, and generally for a short term of service’; also requests instructions and funds to procure food and supplies; has had no answer to repeated letters to War Department . . . .

Moreover, in a letter to Confederate Secretary of War George W. Randolph, dated December 8, 1862, and sent from Bonham, Roberts signed off as “Lt. Col & A. A. G.”

A couple of months earlier, Roberts was introduced by mail to Secretary Randolph by President Davis. In his letter, dated October 23, Davis wrote: “This will introduce to you Col. [Samuel A.] Roberts of Texas who will explain to you some important matters connected with the service in the Indian Country, and of which I will subsequently confer with you.” Of Roberts, Davis wrote: “An acquaintance of many years enables me to speak confidently of Col. Roberts as a true and reliable gentleman. Commending him to your polite attention.”

(Sources note that copies of correspondence between Roberts and Davis are on file with the National Archives.)

It is possible that Roberts was mailing all of his war-related correspondence from the camp bearing his name. The Texas State Handbook notes that Camp Roberts, “the training camp for Confederate soldiers at Bonham,” was named for Samuel A. Roberts.

In August 1863 Union forces in the Indian Territory were steadily pushing south, making Confederate forces in north Texas understandably nervous. On August 26, Union soldiers under the command of Maj. Gen. James Blunt routed Confederate forces at the supply depot in Perryville (roughly south of present-day McAlester, Oklahoma).

In response, Confederate Brig. General S. P. Bankhead set out to reinforce rebel forces in that area. He called on Col. Roberts at Bonham to be ready to help him. Roberts detailed the whole affair in a letter, dated August 29, sent to a Captain Edmund P. Turner, Assistant Adjutant General in Houston, advising him:

At a very early hour on the 28th, I received a dispatch from General Bankhead, informing me that the enemy was driving General Steele before him, and that General S. had fallen back to Perryville . . . and urging me to cooperate with him, General Bankhead, in every way I could to strengthen and subsist his army. I immediately issued an order . . . directing the majors of five different battalions to hold one company in readiness to march at a moment’s notice. This order was sent to each battalion yesterday morning by express, and reached them last night. I have ordered the ordnance officer here to have every gun, of every description, put in order for immediate use, cartridges prepared, &c. I have also taken measures to secure all the ferry-boats on Red River.

It seems doubtful that “every gun” could have been “put in order for immediate use . . . .” Towards the end of the letter, Roberts noted that most of the arms at the Bonham post were “unfit for use,” and that many could “never be rendered serviceable.” He further noted: “State troops are entirely without arms . . . .” In a final plea, he wrote: “If a few stand of arms could be sent to this command, they would be of great benefit.”

In the opening paragraph of his letter to Captain Turner, Roberts noted that he had “assumed command of the Northern Sub-District on the morning of the 28th (yesterday).” Whether to his relief or dismay, his time in that position was very brief. Also on the 29th came a special order, from the “Headquarters District of Texas,” placing Brig. Gen. H. E. McCulloch in “command of the Northern Sub-District of Texas, with headquarters at Bonham.”

Perhaps reflective of his new position, in a subsequent document, dated September 30, 1863, Roberts signed off simply as “Lt. Col., Comndng Post Bonham.” Maybe by “Post Bonham” he was referring to Camp Roberts.

It seems safe to assume that Roberts’ service in the Civil War kept him in the North Texas area and close to home most of the time. One general description notes that he “was colonel of the 14th Brigade, TX State Troops, which later became part of the 34th Cavalry/2nd TX Squadron.”

If the Confederacy’s eventual loss to the Union in 1865 was a sad event for Samuel Roberts, it was overshadowed by the fact that his wife, Lucinda, died the same year. However, personal sorrow on this level was nothing new. From the early 1840s to the early 1850s, he and Lucinda lost three children, a daughter named Florence, and two sons, Samuel Jr. and Clarence.

With the war over and his wife gone, it was time for Samuel A. Roberts to re-focus on his law practice and enjoy the company of his surviving child, a sixteen-year-old daughter named Mary.

Samuel A. Roberts’ final years

In its biography of Samuel A. Roberts, the Texas State Handbook notes: “On April 8, 1842, Roberts married Lucinda Mary Reed. The couple moved to Bonham, where Roberts entered a law partnership with James W. Throckmorton . . . and Thomas J. Brown.” A casual reading of those sentences and the reader might assume that Roberts began practicing law with Throckmorton and Brown in 1842. A little clarification is needed.

While it is true that Roberts began practicing law in Bonham in the 1840s, his partnership with James W. Throckmorton, a future governor of Texas and congressman from the state’s third district, and Thomas J. Brown, a future justice and chief justice of the Texas Supreme Court, probably didn’t start until the mid to late 1860s. In the early 1840s, Throckmorton (born 1825) and Brown (born 1836) were too young to be lawyers.

While their paths, professional or otherwise, may have passed in the 1850s, there is ample evidence that the Civil War was the event that allowed Roberts to get acquainted, or perhaps better acquainted, with both men. Throckmorton, as a commander of the northern frontier district in Texas, was frequently through Bonham to confer with local commanders such as Roberts and Gen. Henry E. McCulloch. Moreover, there is ample documentation, much of it on the internet, showing that Throckmorton frequently sent correspondence from Bonham.

Similarly, Thomas Brown was undoubtedly through Bonham occasionally as a member of Robert H. Taylor’s regiment of the Twenty-Second Texas Cavalry.

Evidence indicates that it may have been the post-war period when Roberts teamed up with Throckmorton and Brown to form a law practice. In her biography of Samuel B. Maxey, the lawyer and former Confederate leader from Paris, historian Louise Horton wrote: “The Bonham firm of Samuel A. Roberts, J. W. Throckmorton, and Thomas J. Brown . . . often hired Maxey to assist with their cases.” Horton’s sources show that Maxey did such work in the late 1860s.

While they worked closely with Roberts in Bonham, Throckmorton and Brown lived in McKinney and had a partnership there as well.

In addition to his law practice, Roberts apparently kept busy with personal correspondence. If he thought the close of the Civil War meant that he would never hear from his old commander-in-chief again, imagine his surprise in May 1870 when he received a letter from Jefferson Davis. The Papers of Jefferson Davis (LSU Press, volume 12, 1865-1870) describes the letter as follows: “[W]ritten to West Point classmate, a lawyer in Bonham, Texas . . . .” Davis referred an old friend of his, Francis A. Wolff, to Roberts. Wolff, he wrote, was going “to Texas, ‘to seek his fortune.’” Davis also noted: “Any attention you may show to Mr. Wolff will be recognized as a personal favor done to your school fellow and personal friend.”

By the spring of 1871 Samuel A. Roberts perhaps felt that his health was failing him, for he clearly decided it was time to get his personal affairs in order. Courthouse documents show that his will was filed on May 19.

Possible failing health aside, on the personal front the spring of 1872 brought reason to celebrate when his daughter, Mary, married a local man named Joseph Anthony.

Unfortunately, fate did not allow much time to enjoy the company of the newlyweds. Just four months later, on August 18, Samuel A. Roberts died in Bonham. He was sixty-three years old.

Shortly after his death, when the district court of Fannin County went back into session on September 2nd, attorneys, including Thomas J. Brown, and others present paused, as their first order of business, to reflect on the life of their colleague. The following was read (the unusual spelling, prevalent at the time, bad grammar, punctuation, etc. are in the original document found in Book D of the Civil Court Minutes):

Whereas, by the dispensation of an Allwise Providence our associate, friend and Brother Col. Saml A. Roberts, has been removed from our midst and from earth. _ And whereas. By long and friendly associations both at the bar and in the walks of social intercourse we had learned to appreciate his many virtues and estimate his great abilities and his usefulnefs to his Society and his State_. Therefore, be it Resolved that in the death of our brother we mourn the lofs of the nestor of the Fannin Bar. And a friend who was bound to us by “hooks of steel”, Society a conservator whose laws bear the imprefs of his matchlefs virtue and the State a citizen who has labored long and earnestly to brighten her Star and add fresh Glory to her history_ Coming to Texas in the early and uncertain days of the Republic the voice of our deceased brother has been heard in the Councils of State and the halls of Legislature – and the laws of the land and wisest provisions of the Constitution remain imperishable monuments to his genius_ He has gone from Earth but he still lives – on earth through the result of his earnest life work and in Heaven through his Stainlefs Spirit_

Resolved – that as members of the bar and late associates of brother Roberts we hereby tender to the family of the deceased our warmest and most heartfelt sympathies.

Court then adjourned until the next morning.

When writing, roughly thirty-seven years later, about his close relationship with Roberts, Judge W. A. Evans noted:

His kindness to me was such that I can never forget him. He had a good law library and built a nice brick office on the north side of the square. After he completed that office, he gave me office room and the use of his library and aided me in getting a start in the practice of law.

Exactly where Samuel A. Roberts was laid to rest is unknown. However, evidence strongly indicates that it must have been in Inglish Cemetery. First, in his will Roberts clearly wrote: “I desire my [body] to be buried by the side of my beloved wife in my family burying lot near Bonham.”

According to Judge W. A. Evans, in his biography of Roberts that ran in the March 6, 1909Bonham Daily Favorite, Roberts’ wife, Lucinda, was buried in Inglish Cemetery. He further noted that Roberts’ was buried next to her. (In my first piece on Roberts, I noted that Evans erred when he called Roberts a West Point graduate. However, it is hard to believe that he would get a local fact such as the location of his “honored grave” wrong.)Secondly, Inglish Cemetery was the most prominent local cemetery “near Bonham” at the time, and it seemed a proper place for Roberts since it was the final resting place of other political notables who preceded him in death, such as Bailey Inglish, Daniel Rowlett and Col. James Tarleton.Finally, Roberts’ daughter, Mary, was ultimately buried in Inglish Cemetery (1887) as well. Her burial spot is in a fenced family plot belonging to her husband and his parents, and it is assumed that they probably chose a spot near the graves, perhaps unmarked even then, of Mary’s parents and siblings.In the end, how ironic it is that a man who left an indelible mark wherever he went, be it West Point, the early days of the Republic of Texas, courts of law or the Civil War, lies in an utterly unmarked place.

All images of the Roberts family are courtesy of Sarah Taliaferro. Many thanks to Mr. Roy Isbell and his excellent research source. Also, many thanks to the ladies at the Sam Rayburn Library and the Bonham Public Library for help with Mirabeau B. Lamar resources. And to the ladies at the district clerk’s office for help with old court documents.